- Home

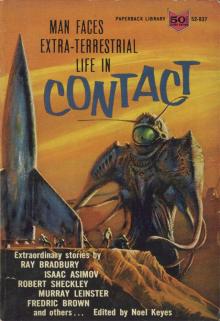

- Noel Keyes

Contact Page 8

Contact Read online

Page 8

“Funny, but I’m not sleepy,” I said. “I think I’ll drop around to the museum.”

My wife said that was what she liked about me, that I never tired of places like museums, police courts and third-rate night clubs.

Anyway, aside from a racetrack, a museum is the most interesting and unexpected place in the world. It was unexpected to have two other men waiting for me, along with Mr. Lieberman, in his office. Lieberman was a skinny, sharpfaced man of about sixty. The government man, Fitzgerald, was small, dark-eyed, and wore gold-rimmed glasses. He was very alert, but he never told me what part of the government he represented. He just said “we”, and it meant the government. Hopper, the third man, was comfortable-looking, pudgy, and genial. He was a United States senator with an interest in entomology, although before this morning I would have taken better than even money that such a thing not only wasn’t, but could not be.

The room was large and square and plainly-furnished, with shelves and cupboards on all walls.

We shook hands, and then Lieberman asked me, nodding at the creel, “Is that is?”

“That’s it.”

“May I?”

“Go ahead,” I told him “It’s nothing that I want to stuff for the parlor. I’m making you a gift of it.”

“Thank you, Mr. Morgan,” he said, and then he opened the creel and looked inside. Then he straightened up, and the other two men looked at him inquiringly.

He nodded. “Yes.”

The senator closed his eyes for a long moment. Fitzgerald took off his glasses and wiped them industriously. Lieberman spread a piece of plastic on his desk, and then lifted the thing out of my creel and laid it on the plastic. The two men didn’t move. They just sat where they were and looked at it.

“What do you think it is, Mr. Morgan?” Lieberman asked me.

“I thought that was your department.”

“Yes, of course. I only wanted your impression.”

“An ant. That’s my impression. It’s the first time I saw an ant fourteen, fifteen inches long. I hope it’s the last.”

“An understandable wish,” Lieberman nodded.

Fitzgerald said to me, “May I ask how you killed it, Mr. Morgan?”

“With an iron. A golf club, I mean. I was doing a little fishing with some friends up at St. Regis in the Adirondacks, and I brought the iron for my short shots. They’re the worst part of my game, and when my friends left, I intended to stay on at our shack and do four or five hours of short putts. You see—

“There’s no need to explain,” Hopper smiled, a trace of sadness on his face. “Some of our very best golfers have the same trouble.”

“I was lying in bed, reading, and I saw it at the foot of my bed. I had the club—”

“I understand,” Fitzgerald nodded.

“You avoid looking at it,” Hopper said.

“It turns my stomach.”

“Yes—yes, I suppose so.”

Lieberman said, “Would you mind telling us why you killed it, Mr. Morgan.”

“Why?”

“Yes—why?”

“I don’t understand you,” I said. “I don’t know what you’re driving at.”

“Sit down, please, Mr. Morgan,” Hopper nodded. “Try to relax. I’m sure this has been very trying.”

“I still haven’t slept. I want a chance to dream before I say how trying.”

“We are not trying to upset you, Mr. Morgan,” Lieberman said. “We do feel, however, that certain aspects of this are very important. That is why I am asking you why you killed it. You must have had a reason. Did it seem about to attack you?”

“No.”

“Or make any sudden motion toward you?”

“No. It was just there.”

“Then why?”

“This is to no purpose,” Fitzgerald put in. “We know why he killed it.”

“Do you?”

“The answer is very simple, Mr. Morgan. You killed it because you are a human being.”

“Oh?”

“Yes. Do you understand?”

“No, I don’t.”

“Then why did you kill it?” Hopper put in.

“I was scared to death. I still am, to tell the truth.” Lieberman said, “You are an intelligent man, Mr. Morgan. Let me show you something.” He then opened the doors of one of the wall cupboards, and there eight jars of formaldehyde and in each jar a specimen like mine—and in each case mutilated by the violence of its death. I said nothing. I just stared.

Lieberman closed the cupboard doors. “All in five days,” he shrugged.

“A new race of ants,” I whispered stupidly.

“No. They’re not ants. Come here!” He motioned me to the desk and the other two joined me. Lieberman took a set of dissecting instruments out of his drawer, used one to turn the thing over and then pointed to the underpart of what would be the thorax in an insect.

“That looks like part of him, doesn’t it, Mr. Morgan?”

“Yes, it does.”

Using two of the tools, he found a fissure and pried the bottom apart. It came open like the belly of a bomber; it was a pocket, a pouch, a receptacle that the thing wore, and in it were four beautiful little tools or instruments or weapons, each about an inch and a half long. They were beautiful the way any object of functional purpose and loving creation is beautiful—the way the creature itself would have been beautiful, had it not been an insect and myself a man. Using tweezers, Lieberman took each instrument of the brackets that held it, offering each to me. And I took each one, felt it, examined it, and then put it down.

I had to look at the ant now, and I realized that I had not truly looked at it before. We don’t look carefully at a thing that is horrible or repugnant to us. You can’t look at anything through a screen of hatred. But now the hatred and the fear was dilute, and as I looked, I realized it was not an ant although like an ant. It was nothing that I had ever seen or dreamed of.

All three men were watching me, and suddenly I was on the defensive. “I didn’t know! What do you expect when you see an insect that size?”

Lieberman nodded.

“What in the name of God is it?”

From his desk, Lieberman produced a bottle and four small glasses. He poured and we drank it neat. I would not have expected him to keep good Scotch in his desk.

“We don’t know,” Hopper said. “We don’t know what it is.”

Lieberman pointed to the broken skull, from which a white substance oozed. “Brain material—a great deal of it.”

“It could be a very intelligent creature,” Hopper nodded. Lieberman said, “It is an insect in developmental structure. We know very little about intelligence in our insects. It’s not the same as what we call intelligence. It’s a collective phenomenon—as if you were to think of the component parts of our bodies. Each part is alive, but the intelligence is a result of the whole. If that same pattern were to extend to creatures like this one—”

I broke the silence. They were content to stand there and stare at it.

“Suppose it were?”

“What?”

“The kind of collective intelligence you were talking about.”

“Oh? Well, I couldn’t say. It would be something beyond our wildest dreams. To us—well, what we are to an ordinary ant.”

“I don’t believe that,” I said shortly, and Fitzgerald, the government man, told me quietly, “Neither do we. We guess.”

“If it’s that intelligent, why didn’t it use one of those weapons on me?”

“Would that be a mark of intelligence?” Hopper asked mildly.

“Perhaps none of these are weapons,” Lieberman said. “Don’t you know? Didn’t the others carry instruments?” ‘They did,” Fitzgerald said shortly.

“Why? What were they?”

“We don’t know,” Lieberman said.

“But you can find out. We have scientists, engineers—good God, this is an age of fantastic instruments. Have them taken apart!”<

br />

“We have.”

‘Then what have you found out?”

“Nothing.”

“Do you mean to tell me,” I said, “that you can find out nothing about these instruments—what they are, how they work, what their purpose is?”

“Exactly,” Hopper nodded. “Nothing, Mr. Morgan. They are meaningless to the finest engineers and technicians in the United States. You know the old story—suppose you gave a radio to Aristotle? What would he do with it? Where would he find power? And what would he receive with no one to send? It is not that these instruments are complex. They are actually very simple. We simply have no idea of what they can or should do.”

“But there must be a weapon of some kind.”

“Why?” Lieberman demanded. “Look at yourself, Mr. Morgan—a cultured and intelligent man, yet you cannot conceive of a mentality that does not include weapons as a prime necessity. Yet a weapon is an unusual thing, Mr. Morgan. An instrument of murder. We don’t think that way, because the weapon has become the symbol of the world we inhabit Is that civilized, Mr. Morgan? Or is the weapon and civilization in the ultimate sense incompatible? Can you imagine a mentality to which the concept of murder is impossible—or let me say absent. We see everything through our own subjectivity. Why shouldn’t some other—this creature, for example—see the process of mentation out of his subjectivity? So he approaches a creature of our world—and he is slain. Why? What explanation? Tell me, Mr. Morgan, what conceivable explanation could we offer a wholly rational creature for this—” pointing to the thing on his desk. “I am asking you the question most seriously. What explanation?”

“An accident?” I muttered.

“And the eight jars in my cupboard? Eight accidents?”

“I think, Dr. Lieberman,” Fitzgerald said, “that you can go a little too far in that direction.”

“Yes, you would think so. It’s a part of your own background. Mine is as a scientist. As a scientist, I try to be rational when I can. The creation of a structure of good and evil, or what we call morality and ethics, is a function of intelligence—and unquestionably the ultimate evil may be the destruction of conscious intelligence. That is why, so long ago, we at least recognized the injunction, ‘thou shalt not kill!’ even if we never gave more than lip service to it. But to collective intelligence, such as this might be a part of, the concept of murder would be monstrous beyond the power of thought.”

I sat down and lit a cigarette. My hands were trembling. Hopper apologized. “We have been rather rough with you, Mr. Morgan. But over the past days, eight other people have done just what you did. We are caught in the trap of being what we are.”

“But tell me—where do these things come from?”

“It almost doesn’t matter where they come from,” Hopper said hopelessly. “Perhaps from another planet—perhaps from inside this one—or the moon or Mars. That doesn’t matter. Fitzgerald thinks they come from a smaller planet, because their movements are apparently slow on earth. But Dr. Lieberman thinks that they move slowly because they have not discovered the need to move quickly. Meanwhile, they have the problem of murder and what to do with it. Heaven knows how many of them have died in other places—Africa, Asia, Europe.”

“Then why don’t you publicize this? Put a stop to it before it’s too late!”

“We’ve thought of that,” Fitzgerald nodded. “What then—panic, hysteria, charges that this is the result of the atom bomb? We can’t change. We are what we are.”

“They may go away,” I said.

“Yes, they may,” Lieberman nodded. “But if they are without the curse of murder, they may also be without the curse of fear. They may be social in the highest sense. What does society do with a murderer?”

“There are societies that put him to death—and there are other societies that recognize his sickness and lock him away, where he can kill no more,” Hopper said. “Of course, when a whole world is on trial, that’s another matter. We have atom bombs now and other things, and we are reaching out to the stars—”

“I’m inclined to think that they’ll run,” Fitzgerald put in. “They may just have that curse of fear, Doctor.”

“They may,” Lieberman admitted. “I hope so.”

But the more I think of it the more it seems to me that fear and hatred are the two sides of the same coin. I keep trying to think back, to recreate the moment when I saw it standing at the foot of my bed in the fishing shack. I keep trying to drag out of my memory a clear picture of what it looked like, whether behind that chitinous face and the two gently waving antennae there was any evidence of fear and anger. But the clearer the memory becomes, the more I seem to recall a certain wonderful dignity and repose. Not fear and not anger.

And more and more, as I go about my work, I get the feeling of what Hopper called “a world on trial.” I have no sense of anger myself. Like a criminal who can no longer live with himself, I am content to be judged.

What’s He Doing In There?

by FRITZ LEIBER

THE Professor was congratulating Earth’s first visitor from another planet on his wisdom in getting in touch with a cultural anthropologist before contacting any other scientists (or governments, God forbid!), and in learning English from radio and TV before landing from his orbit-parked rocket, when the Martian stood up and said hesitantly, “Excuse me, please, but where is it?”

That baffled the Professor and the Martian seemed to grow anxious—at least his long mouth curved upward, and he had earlier explained that it curling downward was his smile—and he repeated, “Please, where is it?”

He was surprisingly humanoid in most respects, but his complexion was textured so like the rich dark armchair he’d just been occupying that the Professor’s pin-striped gray suit, which he had eagerly consented to wear, seemed an arbitrary interruption between him and the chair—a sort of Mother Hubbard dress on a phantom conjured from its leather.

The Professor’s Wife, always a perceptive hostess, came to her husband’s rescue by saying with equal rapidity, “Top of the stairs, end of the hall, last door.”

The Martian’s mouth curled happily downward and he said, “Thank you very much,” and was off.

Comprehension burst on the Professor. He caught up with his guest at the foot of the stairs.

“Here, I’ll show you the way,” he said.

“No, I can find it myself, thank you,” the Martian assured him.

Something rather final in the Martian’s tone made the Professor desist, and after watching his visitor sway up the stairs with an almost hypnotic softly jogging movement, he rejoined his wife in the study, saying wonderingly, “Who’d have thought it, by George! Function taboos as strict as our own!”

“I’m glad some of your professional visitors maintain ’em,” his wife said darkly.

“But this one’s from Mars, darling, and to find out he’s—well, similar in an aspect of his life is as thrilling as the discovery that water is burned hydrogen. When I think of the day not far distant when I’ll put his entries in the cross-cultural index . . .”

He was still rhapsodizing when the Professor’s Little Son raced in.

“Pop, the Martian’s gone to the bathroom!”

“Hush, dear. Manners.”

“Now it’s perfectly natural, darling, that the boy should notice and be excited. Yes, Son, the Martian’s not so very different from us.”

“Oh, certainly,” the Professor’s Wife said with a trace of bitterness. “I don’t imagine his turquoise complexion will cause any comment at all when you bring him to a faculty reception. They’ll just figure he’s had a hard night—and that he got that baby-elephant nose sniffing around for assistant professorships.”

“Really, darling! He probably thinks of our noses as disagreeably amputated and paralyzed.”

“Well, anyway, Pop, he’s in the bathroom. I followed him when he squiggled upstairs.”

“Now, Son, you shouldn’t have done that. He’s on a strange

planet and it might make him nervous if he thought he was being spied on. We must show him every courtesy. By George, I can’t wait to discuss these things with Ackerly-Ramsbottom! When I think of how much more this encounter has to give the anthropologist than even the physicist or astronomer . . .” He was still going strong on has second rhapsody when he was interrupted by another high-speed entrance. It was the Professor’s Coltish Daughter.

“Mom, Pop, the Martian’s—”

“Hush, dear. We know.”

The Professor’s Coltish Daughter regained her adolescent poise, which was considerable. “Well, he’s still in there,” she said. “I just tried the door and it was locked.”

“I’m glad it was!” the Professor said while his wife added, “Yes, you can’t be sure what—” and caught herself. “Really, dear, that was very bad manners.”

“I thought he’d come downstairs long ago,” her daughter explained. “He’s been in there an awfully long time. It must have been a half hour ago that I saw him gyre and gimbal upstairs in that real gone way he has, with Nosy here following him.” The Professor’s Coltish Daughter was currently soaking up both jive and Alice.

When the Professor checked his wristwatch, his expression grew troubled. “By George, he is taking his time! Though, of course, we don’t know how much time Martians. . . I wonder.”

“I listened for a while, Pop,” his son volunteered. “He was running the water a lot.”

“Running the water, eh? We know Mars is a water-starved planet. I suppose that in the presence of unlimited water, he might be seized by a kind of madness and . . . But he seemed so well adjusted.”

Then his wife spoke, voicing all their thoughts. Her outlook on life gave her a naturally sepulchral voice.

“What’s he doing in there?”

Twenty minutes and at least as many fantastic suggestions later, the Professor glanced again at his watch and nerved himself for action. Motioning his family aside, he mounted the stairs and tiptoed down the hall.

He paused only once to shake his head and mutter under his breath, “By George, I wish I had Fenchurch or von Gottsschalk here. They’re a shade better than I am on intercultural contracts, especially taboo-breakings and affronts . . .”

Contact

Contact