- Home

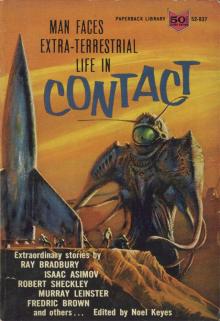

- Noel Keyes

Contact Page 6

Contact Read online

Page 6

Flaring brightness swept the counter, the far wall, settled on the tables, and died a swift yellow death.

“Another car!” whispered the girl.

Kelland went to the door.

“I locked it,” said Schmidt. “We must not trap anybody else, but try to send them for help.”

The shadowy figure of a woman came hurrying up the walk. Through the glass panel of the door, light fell on her as she reached for the knob.

“Please let me in,” she called shrilly. “I must make a phone call—it’s important.”

Kelland came alongside Schmidt. “The phone isn’t working. We’re in serious trouble. Get away and send the police.”

“All I want is to make a telephone call. I simply must! Let me in—I’ll pay you well for staying open five minutes longer.”

“She probably could, too,” muttered Kelland. “She’s money.” Through the door the light gleamed on an evening dress, a fur stole, some jewelry, undoubtedly expensively real.

Schmidt repeated: “We are in trouble. The telephone does not work. Send the police.”

Kelland could have sworn she stamped her feet without moving them. She came close to the glass and peered in. “Unlock this door. Let me in!”

Incredibly, there appeared a small automatic in her hand. “Hey!” Kelland murmured. “That thing could shoot through a door—even this one.”

Confirming this, the gun spat. Something made a spider web of cracks in the glass, and whanged into a pot behind the counter.

“It is no use being killed by a foolish woman,” muttered

Schmidt. “But we must get the gun before she finds out—” And he turned the key.

The woman swept in, made straight for the phone, and took off the receiver with her left hand, the automatic still in her right. Kelland slouched over to her.

“Sorry,” she said insincerely. “I was just desperate to reach a phone. Where is that operator?”

“Let me hold that,” said Kelland easily. He gently took the gun. She flashed him a mechanical smile, and frowned into the unresponsive phone.

“We told you it was out of order,” Kelland murmured. “Drat! How far to the next one?”

“I don’t know. It’s not so simple, you see.”

“You’re not going to make a fuss about that shot? I have a permit.” She opened her bag and held out her hand for the gun. Kelland shook his head.

“Later,” he said.

“It’s mine. I want it now. I’m leaving at once.”

“Okay. But not with the gun.”

Again that invisible stamp of her foot. She turned in a swish of skirt and made for the door, oblivious to the floating cube. Kelland, Schmidt and Kathie watched her in a mutual state of suspense. She threw the inner door open and reached for the screen door.

A minute later she turned panting, to glare at them.

“You’ll pay for this. I demand you release me.”

“Can’t,” said Kelland. “Like we told you, we’re in trouble here. If you’d listened, you might have got us out.”

Kathie stepped up and took her arm gently. “Come with me. We’ll talk.”

“Who wants to talk? This is practically kidnap—” It was then her eyes fell on the cube. She looked from it to the others with the dawning of fear in her eyes. Then they fastened on the cube and did not leave it even while she followed Kathie dumbly into the back room.

“We are no farther along,” said Schmidt when the men were alone.

“I wouldn’t say that. We have this to experiment with.” Kelland waggled the gun. “But that can wait until they get back.”

He was on his second cigarette when they reappeared. The woman in the fur stole sat down on the farthest stoll, her eyes averted from the cube.

Kelland crushed out his smoke. “Now look, maybe a bullet will get through this what-is-it. It mayn’t do any good, but I’m going to try. At least the noise might make a car stop.” Nobody answered him. He waited until headlights approached, aimed the gun through the open door into the ground, and fired. The explosion thundered deafeningly in the little room.

At his feet, rolling off the door saddle, was an oblong little object with a wisp of smoke rising from it. Kelland picked the bullet up with his handkerchief. It felt hot even through the cloth, but it was not at all deformed.

“You know what? I think we learned something.” Carefully he closed and locked the door.

“That not even a bullet can get out?” Schmidt shook his head. “That does not help us.”

“Any information may help. This steel-jacketed bullet wouldn’t mushroom like a lead one, but it would show some sign of ordinary impact if stopped at this range by anything harder than a bale of cotton. This thing isn’t any form of matter as we know it. It’s a force field. Wish I remembered my college physics.”

“I do,” said Kathie. “There was nothing like this.”

“There is now. A field of flux in space, invisible but real enough to absorb kinetic energy by converting it to heart.”

“I want to get out!” whispered the woman.

“So we have some kind of field forming a very effective matter trap. Why? Set by whom? Can we rule out the chance that it’s a freak natural phenomena of some kind? Something that has happened before, unknown because the people who’ve been caught in it—”

“I really must go,” murmured the woman in the evening gown, and suddenly dashed for the door. She turned the key before Kathie and Kelland came and drew her away. His eyes signaled to Kathie, and she took the other woman once more into the back room.

“Another go at that wall and we’d have had hysterics on our hands,” muttered Kelland. “Now that we’re alone, you’d better tell me.”

“I do not know what you mean,” said Schmidt.

“You do, but I don’t—yet. Spill it.”

Schmidt passed a hand over his face. “Not even Kathie did I tell. I was afraid she might think I—”

“After all this she wouldn’t.”

Schmidt drew a deep breath. “It was two nights ago—after Henry Wilcox told about the flying saucer and they laughed at him. Friday night. I locked the pump at eleven. There was a little moon, and some fog but not much. When I came back I saw it.”

“Same as Wilcox saw?”

“Something like what he said. Something as big as the house, round or maybe egg shaped, hanging over it. The fog made it hard to see, but something—something I will swear was up there. It made no noise and had no lights, but it was there.”

Kelland lit another cigarette. “You and Wilcox, then, saw something you can’t describe. Doesn’t help much, does it?”

His gaze fell on the cube. “Seems logical that the force field starts from that thing. What if we could destroy it?”

“It is like the door and the windows,” said Schmidt. “You cannot even touch it.”

On one knee beside the cube, Kelland thrust his pocket knife at it. The blade scraped an invisible, glass-smooth surface. It was like trying to cut solid air. Kelland thought of the cleaver, but his earlier attempt with it promised little chance in that direction.

“Looks as if direct action is a blind alley in this case. They wouldn’t leave anything vulnerable where we can get to it so easily. The thing could be—”

He stopped as Kathie appeared, alone. “I gave her a sleeping pill. She had them with her.” She looked directly at Kelland. “What could it be? And why did you say ‘they’?”

“Tell her what you saw,” the reporter said to Schmidt, and the older man did so. Kathie looked inquiringly at Kelland.

“You know your father,” he said. “Could he have—imagined it?”

“No.”

“All right, let’s assume he did see something. No machine we have could hover silently. A balloon would drift, unless anchored. So let’s assume it was alien, out of this world.”

The girl nodded tautly.

“Whoever was aboard it was interested in this place for some reason. W

hy? Why wouldn’t beings from another world go to Washington, or the Aberdeen proving grounds, or even the copy room of the Associated Press, rather than a roadside lunch room?”

He ground out his half-smoked cigarette.

“As one wild guess, to try to fit the facts—suppose they want to know something about us before they go near those places or let on they’re around? About Joe Doakes and Mary Jones. How we think, what we do in trouble. How Mr. and Mrs. Ordinary Earthman would react to something altogether outside their experience. Like this situation of ours. Mightn’t they pick just a place like this, people like us, give us our emergency, and see what we do about it?”

Kelland looked squarely at Kathie.

“You think this is strictly from Buck Rogers?”

“No. Oh no.”

Her father raised his hand. “And so—we can only wait.”

“Not wait. Think!” Kelland snapped. “Think fast. If the alien theory is right, there’s a way out.”

“To escape?” asked Kathie. “But why?”

“Because they obviously aren’t taking us anywhere. Because it must be simply an intelligence test. When we study animals, we set them a problem they should be able to solve. We tie bananas in a monkey’s cage, out of climbing reach. Or put a rat in a maze, and food outside. But we leave a stick for the monkey to knock the bananas down with, and there’s a way out of the maze if the rat will only find it.”

Nobody answered. Kelland went behind the counter, laid a newly lit cigarette on the edge of the gas range, and drew a glass of water from the tap. He drank slowly, watching the cigarette smoke spiral upward, trying to marshal his thoughts. A knock on the door scattered them.

“We didn’t lock it again!” he shouted, rushing from behind the counter. But the man was already inside, blinking a little in the glare of the fluorescents.

He was about five feet six, middle aged, dressed in flannels and a sport shirt. He looked embarrassed and vaguely as if he expected something unpleasant to happen.

“Sorry to bother you,” he said. “My wife should be here—I spotted her car as I went by.”

“Slender, good looking, wearing a fur cape over an evening dress?” asked Kelland.

“Yes. She is here, then?”

“She wasn’t feeling well. She’s lying down.”

The man turned to Kathie. “Thank you. Will you tell her I’ve come to take her home?”

“She is in a very nervous state,” said Kathie. “Wouldn’t you care to wait a few minutes, while she rests a bit more?”

“Rests? You mean rot, don’t you? Rot in this filthy little shack.” The woman stood at the door beside the counter. “To think that I left two hours ago with big ideas—and landed here, with Charlie!”

“You were asleep, weren’t you?” murmured Kathie.

“On one pill? It takes three these days, dearie. Why? Look at Charlie.”

“I think we could all use some coffee,” said Kathie desperately.

“He doesn’t know it yet, does he? Poor Charlie.”

“Doris! For heaven’s sake—”

“Don’t Doris me. Where’s that coffee? I could stand some, if there’s nothing better to drink. Coffee for all the monkeys in their cage.” She stared mockingly at Kelland while Kathie put five steaming cups up on the counter, then perched herself on a stool, displaying more nylon than necessary.

“This is my husband, Charles Edding. Mr. and Mrs. Edding, of Southerton.” She spoke to Kelland as if the others were not there. “All set now for the experiment, aren’t we? Mr. and Mrs. Earthman, and friends.”

“Doris, I’m afraid these people won’t understand.”

“Oh no, Charlie. As usual, it’s you who don’t understand. It’ll be fun watching things dawn on you.” She addressed Kelland again. “Charlie’s treasurer of the Johnston plant at Southerton. Tells them whether they’re making money, and how much they can spend. But he’s still just a bookkeeper at heart, and that I can’t stand.”

“Doris, please—”

Kelland grabbed his coffee cup. “That’ll do, Mrs. Edding. Better help us think this thing out instead.”

She swung around on her stool. “Certainly. All the monkeys will now concentrate on their problem. Oh, stop shushing me, Charlie. These people are going to know our naked souls pretty soon, and you fuss about privacy. So I ran away from you for another man, but he stood me up and you found me. Wasn’t that easy?”

Edding stared into his cup. Schmidt plodded over to the door, locked it carefully, and sat down at a table. Kathie brought him a cup of coffee, which he ignored.

At the counter, Doris turned as if against her will to stare at the levitated cube.

“Why don’t you cover that thing up?” she asked. “It gives me the willies. Besides—”

She jerked upright, the cup falling from her fingers. The others saw her eyes freeze with terror, and following her stare, saw the cube pulse with a sudden, inward glow, swiftly blazing from soft silver to a stark and terrible whiteness.

Doris screamed. Kelland felt suddenly as if he had been clapped over both ears. In a low voice Edding spoke to his wife.

“Shut up!” she snapped. “It did something then—my ears popped as if I were coming down in a plane.”

“I felt that too,” said Kathie.

Doris turned to her husband. “Charlie, get me out of here. I’ll go back with you—I’ll stay. Only get me out of here right now.”

“Of course, dear. Of course.” He laid a dollar bill on the counter and turned. Kelland gripped his wrist.

“It isn’t so simple. Your wife hasn’t explained why she is upset, but that white thing is part of it—the lesser part.”

“They’ve been holding me prisoner!” wailed Doris.

Edding stared from her to the cube to Kelland, who speedily explained. “Don’t take my word for it—nobody could. Go and try it yourself.”

As though sleepwalking, Edding went to the door. Four feet from it he cried out in pain and came to a stop, blood trickling from his nose.

Kelland rushed to his side, groped flat-handed in the air from the floor to arm’s length over his head. Schmidt, from his seat by a table, cried out like a child.

“The cup! I cannot reach it—it is on the other side.”

He clawed frantically at nothingness over the table. Jumping on a chair, Kelland continued his exploration overhead. His fingers encountered a surface eight inches below the ceiling.

“Kathie, take the Eddings back and see where the barrier is on that side,” Kelland ordered.

Doris clung hysterically to her husband as Kathie herded them both into the back room. Pulling out a fresh cigarette, Kelland remembered the sudden pressure on his ears, and threw it aside. They might need all the oxygen left.

Then Kathie was back. “It’s three feet inside the windows now. What does it mean?”

“Means we have less room to move around in, and certainly less air to breath. It also means,” said Kelland, “that they’ve pulled the bananas a bit higher, given the maze a spin, to see what their test subjects will do.”

“What can we do?”

“Don’t know. I’ve been trying to remember something that Doris knocked out of my head. No, it was Charlie. I was standing by the stove.”

“You got a drink of water.”

“Yes, I remember thinking that water ran down the drain all right. That could mean the barrier doesn’t go below ground, but nor can we.”

“You laid your cigarette down. I remember watching the smoke go up the ventilator.”

“That’s it!” Kelland strode behind the counter again and stared up at a small, motor-driven fan set into a circular grille. “If the smoke got out—and it did—the barrier didn’t close that grille. We had ventilation—the ventilator shoved air out, and fresh air came in the window. Now it’s different. When they shrank the barrier, the fan was left outside.”

To demonstrate, he climbed on a stool. His hand was stopped two feet from the ven

tilator.

“Whatever it is, the barrier shrinks from the outside in, compressing air ahead of it. With no way for it to get out, the air pressure in here must be slightly above that outside. That was why our ears popped, and why no more fresh air can get in.”

“You mean we’ll suffocate?”

“I suppose so, in time. But the point is, why did air get out before?”

“Through the grille?” asked Kathie. “It’s nothing but a metal ring.”

“Sure. A ring—a space completely enclosed by metal. Like the drain pipes. Maybe a ring detours the barrier. If so, couldn’t you push stuff through the ring?”

Kathie stared as he pulled the gun from his pocket. “The gun barrel is a cylinder.—I wonder—a stretched-out ring.” He spread his left hand against the invisible wall before him, fingers apart. Into the V between thumb and forefinger he thrust the barrel. Kathie gasped as it slid an inch beyond his hand.

“See that? It slides through. I think the bullet would get out if I fired, but it’s risky to try. If I’m wrong, the barrel would explode. What else have we got in the shape of a ring?”

“The bag holder in the coffee urn,” said Kathie.

She took off the domed top and withdrew a nickel-plated hoop. From it dangled a sodden cloth bag. She emptied the coffee grounds and gave Kelland the bag. He knelt with it before the barrier. As he pushed the ring toward it, the bag was flattened. The top of the metal hoop struck solidly against empty space.

“It doesn’t work!” Kathie cried.

“No, wait—got to hold it parallel to the barrier so that the whole ring makes contact.” He did so, and felt it sink into that transparent impenetrability. Holding it in position with his fingers inside, he triumphantly pushed the bag through and pulled it back again. From his seat by the table Schmidt half rose in excitement.

“Convinced?” asked Kelland. “I think this is it. Now all we need is a ring big enough to crawl through.”

Kathie shook her head. “But what can we use?”

Kelland looked about. “A screwdriver, first of all.”

She gave him one from under the counter, and he pried up the metal molding from around the counter edge. It came off in an eight-foot strip.

Contact

Contact