- Home

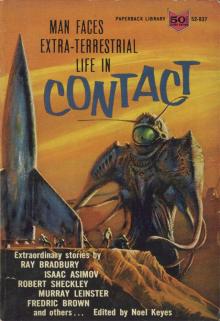

- Noel Keyes

Contact Page 10

Contact Read online

Page 10

“That fits all right then,” he said, “get right down to surface, then move up-river, Mike.”

The sea-plant grew right up the estuary of the little river, leaving a few channels only near the centre for the main flow of water. The valley, with its string of lakes was packed with vegetation. It blanketed the whole bowl, it enclosed every lake—only a pronounced terracing proclaimed that it was not a huge bog.

“Perhaps I’m being wise after the event,” said Britthouse, “but I’m sure I would never have put down in that little set-up. It’s too pretty to be healthy.” His lieutenants nodded agreement. Long experience had taught the Planetary men that life can play strange tricks upon the unwary; as a general principle they keep it at arm’s length until it had been fully docketed. “Why do you suppose he did it?” asked Crofton.

“The idea was good enough,” said the Captain, “he knew his engines were done, and his radio might fail at any moment He had no time to work out a reference-frame for the globe, and with a dead radio he could not give us signals to get a fix on. So he had to find some conspicuous landmark. He certainly did it—but he need not have sat himself plumb in the middle of it. He could have set down on that escarpment back there and still been easy to find. Point is: he’s not there now. Get hold of the Berenice and suggest that we make a base upon the escarpment at the head of the valley and work out a plan.”

Commander Japp, however, demurred. He was accustomed to operating from his ship, to him a planetary surface was either a port or a place to be avoided. Accordingly, he invited Captain Britthouse to his vessel, pointing out the better facilities at his disposal.

“Blast the fool!” said Britthouse, “Facilities my foot! I suppose he means he has a carpet on his chartroom floor.” He turned to his junior officers, “You remain in charge of the ship Mike,” he said, “Bob, tell Sergeant Davys to be ready to receive the picket-boat from the Berenice, and you come with me for moral support. These Interplan stiffs give me the screabies,—and none of this ‘Okay boss’,” he snapped as Crofton replied. “It’s ‘Very Good Sir’, and click your blasted heels when you say it. Come on.”

Britthouse would have shaken hands, but Japp greeted him with a stiff salute and led the way past the guard of honour to the officers’ mess. The Captain was already sufficiently uncomfortable before they were half-way along the spotless corridor. He had not changed out of his service uniform, while Japp was resplendent in the full dress of a Sub-Sector Fleet Commander, Second Class. He gleamed, he rattled, he clinked as he walked along. But when they entered the officers’ mess Britthouse stopped dead in his tracks. A formal dinner was set out, the officers of the Berenice were two rigid ranks of blue and silver, the table gleamed with glass and plate. Britthouse was more than astounded, he was shocked and horrified. Not far away, he thought, twenty men of this very fleet are lost, perhaps in peril of their lives, and this—this popinjay was staging a full-scale formal reception. Tradition hell, he thought, he was not going through with it. He squared his shoulders in the doorway.

“Commander Japp,” he said, “I would like a word with you in private, if you please.” The Commander’s face was expressionless. He had expected this, his trap was ready. His tone when he replied was faintly deprecatory.

“If you feel it to be necessary, Captain Britthouse, very well.” His tone said quite plainly that only a boor from Planetary could be so ill-mannered. He turned to the room, “At ease, gentlemen, we shall not keep you waiting long.”

In his cabin he faced the Planetary man; he stood inches taller than Britt’s chunky figure, in spite of his stoop.

“Well, Britthouse, what is it?” He contrived to be insulting, whether he used the title or not. Britt held a close rein upon his temper.

“I feel, Commander, that this is hardly an appropriate time to indulge in formal hospitality. In my opinion, we should be pushing on with our investigations with the utmost speed. We have no—”

Japp cut the young man short brusquely, “I have already despatched the necessary message,” he said, “the entire Sector Fleet is already on its way at full acceleration, they will arrive in approximately eighty hours. Until then, there is nothing we can do.”

Britt was caught completely off his guard. The unexpectedness of it took his breath away, he was momentarily speechless. “But—but—why call the Fleet?” he stammered eventually, “cannot we deal with the situation?” This was even better than Japp had expected, he sprung his carefully-laid trap.

“It would be quite suicidal, my dear Captain, to tackle a hostile civilisation with only two small vessels. In any case, the action is clearly prescribed in my Standing Orders. I have not the authority to hazard my vessel in the face of organised intelligence.”

If Britt had been astonished before, he was now completely thunderstruck. He wondered which of them had lost his reason—the man might have been talking Andromedan Siltzish for all the sense he could make of it. At length he found a concrete idea to pick on.

“What organised intelligence?” he demanded. “What evidence of organised intelligence have you found?”

“I should have thought it was self-evident,” retorted Japp frostily, “a Mark IX Light Cruiser, inertial mass 8,000 tons, vanishes completely within twenty hours of landing beside an obviously artificial watercourse, leaving no trace. Only organised intelligence would have the means to transport an object of that size in the time without leaving the most obvious traces. But, more significant still, only an organised intelligence would want to do such a thing. What non-intelligent creatures would approach an unknown object of that size? Or have you an alternative explanation to offer?”

Britt was stumped absolutely. Of course, he had no alternative explanation to offer. He had not even begun to theorise upon the matter—he wanted to collect some facts first, it was much too early to begin hypothesising. Still, there was no hope of explaining this point of view to this . . . this Greek, he knew the type: it would be waste of time to argue with the fellow. He suddenly remembered his rendezvous with Jenny, and was filled with a fierce exasperation and an impulse to be rid of the whole business.

“I am sorry Commander,” he said, “I cannot agree with you. I must beg you to excuse us. I wish to return to my ship immediately.”

No further word was spoken. In complete silence the two Planetary men filed past the ramrod guards and into the picket-boat. Britt was miserably conscious of having made a very bad showing, the situation had been sprung on him out of the blue—it did not occur to him that this may have been deliberate—and he felt that he had spoilt a good case by his reaction. He did not like being rushed into snap decisions, his own instinct was to examine any situation very closely before drawing conclusions. Japp was apparently one of those legendary heroes “famous for his ability to make quick decisions in emergencies.” He had always mistrusted that ability, suspecting that it was simply an incapacity to see more than one possibility at a time. The recent meeting gave him no reason to change his opinion. He realised that it was out of the question to follow his impulse to clear out and leave the impossible Japp to his own devices. As long as there was a chance—however remote—that the men of the Persephone were still alive, he could not leave without doing his utmost.

He renewed his determination to see the affair through within the timelimit—with or without Japp’s assistance, he was not going to miss his date with Jenny.

“So tomorrow,” he concluded in explanation to his lieutenants, “we get out as soon as its daylight and root about beside those musical-comedy lakes to see what goes on around here.”

The planet’s day was about thirty hours, and a pronounced axial obliquity gave them twelve hours of darkness and eighteen of daylight—ideal conditions for a man determined to work himself to death. Britt ruefully supposed that this would be necessary: he had to make his dead-line.

The early start produced a reward at once, the oblique rays from the planet’s sun threw every irregularity into sharp relief, notably a

long oval mound—hitherto imperceptible—of the general shape of the Persephone right beside the red lake. They wasted no time in speculation, Michelson dropped the ship in a breathless dive, grinding to a standstill on the naked rocks beyond the blue belt.

Sergeant Davys was starting up “Jenny”—the tracked all-purpose runabout—as they fell, and within thirty seconds of touching down, Britt, Bob Crofton, and the Sergeant were clanking down the ramp in her. The little vehicle took the steep slope into the valley at an alarming angle, the chrome-molybdenum steel cleats of her treads shrieking and sparking on the rock. Sergeant Davys was an accomplished driver, and the runabout itself was built to take anything that the habitable universe could offer. It was practically indestructible, and its tiny nuclear motors had on one occasion driven it completely submerged through the swamps of Sirius IV under a gravity of 4.2. She did not even falter, therefore, when under Britt’s direction the Sergeant drove her straight into the tangled mass of vegetation.

It was primitive stuff, four-foot stalks each surmounted by a flat disc of a leaf, soft and juicy, looking like nothing so much as a particularly poisonous brand of rhubarb. “Jenny” was in her element, you could see she thought this was chicken-feed. She tore into the stuff with gusto, lurching and skidding on the wet, rubbery stems, churning up a juicy pulp in her tractors. Shreds and tatters of it were flung across the transparent hood, until the Hannibal—guiding from above—was a blurred and rippling caricature.

“O.K. Britt,” said Michelson’s voice in the phones, “it’s a few yards ahead of you now.”

His instruction was unnecessary, the mound was clearly visible from ground level, being no more than an area of the vegetation of greater height than normal. The puzzling, inexplicable thing was that the raised patch was sharply differentiated from the remainder, was almost exactly the length of the missing Persephone, and was on the very spot where the ship had landed.

“Jenny” had churned her way through the length and breadth of the mound twice before they were compelled to admit defeat. Then Michelson had an inspiration.

“What’s the ground like?” he said, “Is she buried down there?” The answer was no, the ground was rock, the naked bones of the planet.

“No soil?” queried Michelson, “Then where does that stuff put its roots?” The answer to this was another negative—the plants had no roots. The stems sprouted from a net-work of cable-like stems lying on the rock. Following the largest of these, they found that some went down into the lakes, some round the lakes, but most ran the full length of the valley, down the beach, and into the sea.

By this time Britthouse was feeling somewhat frustrated. The only clue to the Persephone’s disappearance was the odd little plateau of vegetation, for he was convinced that the plants and the strange coloured lakes were connected with the mystery in some way. It seemed that only a full-scale biosurvey would yield sufficient information upon the nature of the growths. He did not believe that there were any animals at all upon the land-surfaces—let alone intelligent ones. The planet was obviously in an early Silurian stage, and it was by no means certain that there were animals even in the sea, at this early stage.

There were plenty of examples of planets reaching even a late Carboniferous stage without the appearance of animals. His prospects of making his date with Jenny seemed to be receding. Already half a day out of his three had gone with no clear lead. In one of his customary transformations he suddenly snapped out of his mood of concentrated thought and became a humming dynamo of energy. He pieced together a plan for an ultra-rapid survey in five minutes, and within a further ten minutes there were three parties formed from the Hannibal’s tiny complement, feverishly pursuing their assigned plan.

They had an exhausting and surprising day, meeting at dusk on the beach near the estuary, beside the sluggish sea—dead and waveless with the weight of its blue carpet of floating vegetation.

“Right,” said Britthouse, as the hatch closed behind him, “let’s have your reports. Mike?”

“The valley was originally glacial, I think,” he said, “but considerable water-erosion has occurred since. The upper level, above the vegatationline, was certainly a glacial hanging-valley: there is a sharp break in the level and a waterfall. The lakes are a puzzle, geologically, they could be a series of terminal moraines, but they are surprisingly regular. It is very difficult to form any conclusions about the lower valley, as it is entirely blanketed by the vegetation, even the lakes are completely surrounded, and the stuff seems to grow on the bottoms also.

“The large-scale geology is simple enough, this area is a very old eroded plateau; comparing it with other areas in this hemisphere, it is one of the oldest land-surfaces on the planet. Which probably accounts for the fact that this is the largest patch of land-plant on the planet—as far as I have seen, nowhere else does it extend more than a few yards up the beaches or estuaries.”

“That may be significant,” said Britt, “How about you, Bob?”

“Simply a confirmation of what we guessed this morning: all the plant in the whole area is simply one tangled mass of vines, there are no individual plants, the whole mass is one enormous plant. That goes for the sea-plant too, it grows vines up the beach and estuary. The plant in the valley is an extension of the plant in the sea. The leaves are bigger and darker, that’s all. What did you find, Britt?”

“One strange thing: although the plant floats on the surface of the sea, it grows on the bottoms of the lakes.”

“Gravity of sea-water,” said Bob.

“Sure,” replied Britt, “that accounts for why it sinks, but not for why it grows. And it grows all around the lakes too, the water has to seep through yards and yards of it between one lake and the next.”

“What about the colours of the lakes themselves? That’s the most striking thing about the whole set-up from the air.”

“It’s not so startling from ground level,” he said, “but the water is definitely coloured, and a different colour in each lake. Tomorrow we are going to make a tour of them, and draw samples of water from each, and of the vegetation. We shall be doing some analyses. I know it seems remote from our purpose, but I think that if we can get at the reason for the existence of these lakes, we shall have a clue to the disappearance of the Persephone.”

He turned to the signaller, “Have you got that lot on tape?”

“Yes sir.”

“Good. Spool it off and send a copy over to Commander Japp, with my compliments.”

Commander Japp’s reply, received the following morning, was definitely offensive; he begged to inform Captain Britthouse that he was not interested in botanical researches upon the planet, and suggested that the information be reserved for the proper authorities. In point of fact, he was rattled. The activity of the Hannibal’s crew had not escaped his notice, and he had an uneasy suspicion that Britthouse might yet sneak up on him. He remembered having heard some disconcerting whispers about the low cunning of these Planetary people. He fervently wished that they had kept their interfering noses out of an affair that was none of their business. Nevertheless, he felt that some action was now demanded of him, some more detailed theory of the Persephone’s disappearance.

A night of worrying produced no result. It did not occur to him to consult his officers; without conciously expressing the thought, he felt that as Commander he was automatically the person most fitted to solve the problem. A cold shower and a well-served breakfast refreshed him immensely, and he took pencil and paper with the determination to settle this business. He wrote down the substance of his information after the manner of an Euclidean demonstration:—

I. The Persephone, a Mark IX light cruiser of 8,000 tons, lands beside an obviously artificial watercourse with no engines and only enough reserve energy to transmit one distress signal.

II. Within twenty hours the Persephone has vanished and there is no trace of any struggle, or of any machinery used to move her, except a small raised patch of vegetation on the spot

where she presumably landed. (He was not above using Britt’s information).

III. Obviously, therefore, she was moved by air, and the patch of vegetation was a hasty attempt to conceal the spot where she crushed the vegetation.

IV. It follows that we are confronted by a hostile and organised intelligence of some mechanical ability.

V. Standing Orders, Section XVI, Chap. 473, Para. 28673 expressly forbids any attempt by less than three vessels to intervene in such a case, but to call upon nearest Sector Force.

This seemed to be watertight enough, but an attempt at a more detailed explanation would look better, in view of Britthouse’s efforts, blast him. Why had the Persephone been kidnapped? Suppose she had not been kidnapped, but destroyed where she stood, and the blasted area patched up? That seemed even more likely. But why? Suppose the artificial watercourse was of a religious significance, and the builders had destroyed the Persephone in a fit of rage, and then been afraid of the consequences and tried to conceal the murder? He was suddenly elated, this was the solution! The next step followed automatically. As soon as the Sector Fleet arrived they would raze the whole valley as a reprisal, this would inevitably bring the murderers out of their hiding-place, and the Sector Fleet would assume control.

The Sociological Council would protest, of course, but it would be too late. He chuckled to think of the foolish spectacle that Britthouse would make with his detailed description of the trivial botany of a burnt-out valley.

Japp lost no time in drawing up an official report embodying these conclusions, and transmitting it to the approaching Sector Fleet. After a few minutes’ thought, he was reluctantiy forced to the conclusion that he must send a copy to Britthouse also. The young fool’s action in providing copies of his reports put him under the obligation of reciprocating. There was one advantage, he thought with some satisfaction: it would probably stop him fooling about down there.

Contact

Contact